What is magic without ape parts? Inside the illicit trade devastating Nigeria’s apes

Demand for ape body parts for spiritual purposes drives a complex and lucrative trade.

BY ORJI SUNDAY* – Mongabay Series: Great Apes

OHOFIA, Nigeria — The fading sunlight, half-coned and yellow, turns the evening murky. The crowing of roosters mingles with the rattling of motorbikes as farmers make their way home from the field, halting to exchange pleasantries with neighbors.

Sunday Akpa, gun slung across his shoulder, is readying for the night’s hunting. He closely inspects the silvery edge of his machete before gliding it into its sheath, which, like his rounds of ammunition, is strapped about his waist.

“To stay the night in the forest with the invisible powers of natures and darkness, as a hunter, is fearful,” he says. “It requires spiritual powers.”

Sixteen years ago, when he started hunting, Akpa was instructed by a herbalist to obtain ape bones, which would be used to make a charm that would render him invulnerable before wild beasts. His charm, which Akpa still carries with him, is in the form of a powder, which he releases into the wind when faced by wild beasts or spirits.

For Akpa, going to the forest to hunt wild animals is a tradition handed down from his ancestors and one that today earns fame and respect in Ohofia, his tiny village in Nigeria’s southeastern state of Enugu.

But ape poaching in places like Kogi state, where Akpa started his hunting career and still occasionally visits to poach apes, has evolved beyond these traditions. No longer just a small, subsistence activity, ape hunting today is linked to a commercialized trade in body parts that are used as native medicine, trophies, ornaments and in magic, rituals, ceremonies and other cultural practices.

Extending beyond remote villages deep in Nigeria’s forested states, the trade has become a high-volume business that supplies the country’s rapidly expanding towns and cities (Nigeria’s population skyrocketed from 45 million people in 1960 to more than 190 million today), as well as a global market beyond Nigeria’s borders. It is facilitated by modern firearms, cellphones, a vast network of new roads, and logging concessions.

Pushing apes to the brink of extinction

The poaching of apes is a big business, and one whose clandestine nature makes difficult to track.

Estimates of the size and profitability of the bushmeat trade vary wildly: a 2018 study by the U.S.-based think tank Global Financial Integrity estimates the annual value of Africa’s bushmeat trade in gorillas, chimpanzees and bonobos at anywhere from $650,000 to $6 million. Systematic studies of the extent of the trade in body parts are even rarer, but experts say the trade is booming.

The effects of this trade, however poorly understood, are devastating.

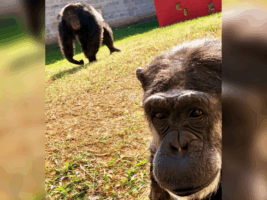

Like nearly all of the world’s great apes, Nigeria’s chimpanzees and gorillas are in a serious decline. The IUCN estimates that the total population of the Nigeria-Cameroon chimpanzee (Pan troglodytes ellioti) now numbers less than 9,000, and likely less than 6,000. About half are found in Nigeria.

While Nigeria’s chimpanzees have been driven to the brink partly by habitat loss and fragmentation, the IUCN describes hunting for bushmeat and body parts as the single greatest threat currently facing this endangered species.

The Cross River gorilla (Gorilla gorilla diehli), whose fragmented habitats straddle the Nigeria-Cameroon border, is the rarest great ape subspecies, with an estimated population of just 200 to 300 individuals. The IUCN estimates that as many as three are killed by hunters each year, a devastating toll for such a critically endangered species.

Due to a lack of data, the trade in ape body parts has often been viewed as simply a by-product of the larger and more profitable trade in wild meat. However, according to ape traders, hunters and a wildlife investigator interviewed for this story, the demand for body parts is a significant driver of ape killing in its own right. In fact, they suggest that it is the meat that is the by-product of a far more lucrative industry that targets apes for their heads, hands, bones and other parts.

Ape parts, not meat, are the profit center

Sources interviewed for this story describe a well-coordinated trade in body parts, with a supply chain that runs from the hunter, who earns the least, through distributors who make large profits, and on to consumers in Nigeria and beyond who seek gorilla and chimpanzee body parts for various purposes, especially charm making.

Unlike the subsistence trade in bushmeat, in which ordinary hunters supply their own households and communities, the trade in ape body parts generally requires financial support and connections to both customers and distribution networks.

This commercialization has brought more money into the trade, increased its complexity, and introduced factors like corruption, bribery and political influence that weaken regulations against ape poaching.

At both the state and federal level, Nigeria has laws and policies aimed at tackling the poaching and trade of endangered species. However, until 2016, Nigeria’s wildlife trafficking law set a penalty of just 1,000 naira (about $5 at the time) for first offenses. That was steeply revised upward to 5 million naira (now about $14,000), but the penalty for repeated offenses remains capped at one year of imprisonment.

In practice, Nigeria’s wildlife protection laws are among the weakest in Africa, says Ofir Drori, who heads Eco Activists for Governance and Law Enforcement (the Eagle Network), an anti-poaching NGO operating in nine African countries. Due to poor implementation, “the law means no risk for traders,” says Drori, one of Africa’s most experienced undercover wildlife investigators.

In addition, the people who finance the trade are powerful and well-connected. Drori describes them as “highly placed people who use their multiple influences to bypass the law, stall convictions in court and sometimes interfere with law enforcement.”

Donatus Chukwu, a retired wildlife trader, concurs. “The process is porous,” he says. “It takes a little bribe to escape. If you pay well enough, the forest guards will allow you hunt and trade, or even facilitate it.”

Drivers of demand

Much of the hunting of Nigeria’s wild animals is driven by a need for protein. In rural, forested communities in Nigeria, bushmeat makes up an estimated 20 percent of the animal protein consumed. It is widely seen as healthier, tastier and often cheaper than meat from domesticated animals.

The trade in ape body parts is driven by more spiritual motives. In much of Nigeria, traditional beliefs in the powers of ape parts still hold sway.

“Ape body parts are the foundation of power in native medicine. To battle spirits, to cast spells, to oppose strongholds in spirit, falls back to ape part powers,” says Chukwu Pius, an influential herbalist from the village of Aru-egwu in Enugu state.

“After all, what is magic without ape parts?” he asks rhetorically.

Pius’s viewpoint is not unique in Nigeria. Although Christianity and Islam are the country’s dominant religions, around 10 percent of Nigeria’s 190 million people still practice traditional religions. (Many of those who officially adhere to monotheistic faiths may also maintain some indigenous beliefs alongside them.) While these indigenous religions vary from locale to locale, they commonly look to nature — rivers, stones, trees and animals — for power.

Practitioners of these traditions — thousands of priests, herbalists, witch doctors, wizards, griots and their millions of adherents — represent a huge market for ape poachers. To many of them, ape body parts are vital items of worship, required for talking to the ancestors, repelling curses, fighting spiritual forces and observing rituals.

Myths about apes are numerous in Nigeria’s multicultural society. These myths, lores and legends vary from community to community but are united in the position that apes share an ancestry with man, command unnatural powers, and remain important in the world of magic.

“To the gods, apes are equal to men. In the metaphysical, the spirit of apes as powerful as the spirit of man. So if the gods need the sacrifice of a man, apes can be used in their place,” says 60-year-old Pius.

Ape body parts are necessary for maintaining some of these practices and belief systems. For instance, among many ethnic groups in Nigeria, especially the Igbos of the country’s east, traditional belief in the power of the spirit of the dead to cause good or harm remains firm. As a result, placing such harmful spirits back in the spiritual world, or limiting their troubles upon the living often requires carefully executed rituals that sometimes involve the use of chimpanzee parts.

“Chaining the spirit of the death requires special charms that cannot be gotten from elsewhere except apes. It is the most powerful animal part in native medicine,” says a renowned seer and a dealer in ape body parts in the southeastern city of Enugu, who goes by the name Hajiya Ibagwa. Ibagwa has been practicing for more than two decades, trading in ape parts and applying them to her charms.

Ape traders say ape heads, hands, feet, skin, urine and bones drive the highest demand. Ibagwa says the most sought-after and expensive ape part is the left hand, seen as holding particular spiritual power. A chimpanzee’s left hand can sell for as much as $100. (Until this year, Nigeria’s monthly minimum wage was just $50.) A gorilla hand can go for twice that.

The most common victims of the trade are chimpanzees, which are relatively abundant. Gorilla parts are scarcer but more profitable due to both the rarity of the species and a widespread belief that their body parts are more potent. “It is every magician’s choice,” explains one elder in Ohofia.

Another cultural practice to which ape parts are applied, according to Ibagwa, is the burial of great hunters and powerful people. Such practices, she adds, are fading away. But in their heyday, they required placing ape bones, or an entire skeleton, into the coffin along with the deceased.

Traditions can change

While traditional beliefs in some parts of Nigeria contribute to ape hunting, in other areas they can have a protective influence. Many communities refrain from eating or harming apes for religious or cultural reasons. For example, some communities view apes as closely related to humans, and thus view eating or even killing chimpanzees and gorillas as evil. Others see apes as demigods worthy of reverence, assigned special powers and purposes by the supernatural.

However, ape traders who front the money for poaching operations have had success in enticing people away from these customs and tradition.

For example, when my late father, a renowned ape trafficker, visited Taraba state in northern Nigeria in the 1980s, he found out that locals culturally abstained from eating or touching apes. He spent years trying to persuade local hunters to kill apes. Eventually, the lure of the riches he promised proved stronger than tradition, and some hunters starting asking for advice on how to kill and sell apes.

From that point on, he established a network of local hunters working under him, who were guaranteed payment for any ape they killed. Like other traders, my father supplied hunters with bullets and arranged for local forest guards to be bribed to look the other way.

It was a cautious trade, carefully planned. The hunters killed apes and hid them in the forest. They would inform my father where the bodies could be found, leaving him to return by night to pluck the catch.

Though my father retired from the trade in 2002, the traders operating today have continued to use the old tricks while also developing new mechanisms to keep the trade running. An apprenticeship system of sorts allows young people to serve under older and more experienced traders who teach them the tricks, secrets and networks of the trade.

Visits to multiple wildlife markets in Lagos and southeastern Nigeria showed that people were still able to buy and sell ape parts freely, albeit cautiously. In these markets, there were no signs of trade restrictions, official monitoring or law enforcement. Traders openly display parts of animals protected by Nigerian wildlife laws, including vultures, kites, jackals and pythons. The trade in ape parts is more discreet. Shops don’t openly display ape parts, and may even keep them offsite, and customers use coded language — asking, perhaps, for “cement” rather than an ape skull. But while traders are generally aware that what they are doing is illegal, they appear to have little fear of repercussions and were willing to discuss their activities with a reporter.

A complex, cross-border business

Not all of Nigeria’s regions have ape populations, but they are all commercially connected to the trade.

Nigeria’s dense forests are concentrated in the states of Bayelsa, Cross River, Edo, Ekiti, Ondo, Osun, Rivers, and Taraba. These states, which are clustered near Nigeria’s southern coast or its border with Cameroon, account for the vast majority of the habitat suitable for apes.

These forested states supply the raw parts for the trade, which are then brought to other regions of the country and even the world. Ape part traders interviewed for this story say Lagos and Ibadan are the hubs for the ape body part trade in western Nigeria. In the east and middle belt, the cities of Enugu and Onitsha are the hubs. Cross River supplies markets across cities in southern Nigeria. In the north, Taraba, which borders Cameroon, and Kano are the hubs for the trade.

As the largest economy in Africa, with a GDP of $376 billion, and an abundance of highly skilled and widely traveled traders, Nigeria is able to exert a powerful but negative impact on the regional ape trade.

“Nigeria is like the coordinating center for ape body part trade in Africa,” says the Eagle Network’s Ofir Drori. “It controls the trade — receiving body parts from Central African countries, West Africa and Cameroon — serving as a channel for smuggling them to other parts of the world. If Nigeria can be changed or controlled, it would cut off a significant, or even the biggest, driver of the business in Africa because once an ape part is smuggled to Nigeria, its value financially increases.”

Ape traders interviewed by Mongabay support this analysis. They say that markets in the Nigerian cities of Lagos, Onitsha and Kano are fed in part by a supply of apes and ape parts from Cameroon and elsewhere in West and Central Africa. After being trafficked across borders, these stocks are blended with locally sourced parts and packaged, polished and shipped to markets in growing urban centers, far-flung rural communities and even overseas to Asia, Europe and the United States, where they are applied to fetish uses, souvenirs and decorative functions, and when captured alive, as pets and trophies.

Ekene Ezenwoke, an Enugu-based ape-part trader, says that ape parts can be found in many Nigerian cities. Even in major markets that are not devoted to bushmeat, body-part traders often run small, clandestine shops. But when he wants a large quantity, he reverts to Lagos, which he says is the “ape part headquarters in Nigeria.”

Tackling the trade

The trade’s complex trajectory has made it very difficult for law enforcement agencies to tackle traffickers. Most anti-ape poaching campaigns, advocacy programs and law enforcement efforts focus on states where apes are found.

The aim, understandably, is to protect ape habitats and cut traffickers’ supplies at the root. But in reality, much of the trade takes place in locations that are geographically far from these targeted states.

In the absence of a collective strategy to combat the bushmeat trade in great apes from African governments and NGOs like the Nigeria Conservation Foundation, the Eagle Network and the Wildlife Conservation Society (WCS) advocate for better law enforcement, more support and training for park rangers and forest guards, the provision of alternative livelihoods for hunters, and awareness-raising efforts that bring communities into the center of ape conservation efforts.

While this approach has evident value, its impact is limited where villagers place a premium on survival rather than conservation ideals, says Emmanuel Owan of the Nigeria Conservation Foundation. Unless attractive alternatives are provided, he says poaching is likely continue despite legislation and advocacy.

But the trade in ape parts runs deeper than just economics. What may be even more complex to tackle are ancient traditions that call for chaining the spirits of the dead, aiding childbirth, and healing seizures with charms whose potency are believed to come from ape body parts.

Disclosure: Orji Sunday’s late father was an ape part trader. No other family members, including Sunday, have been involved in the trade, and Sunday does not have personal connections to any of the people interviewed for this story.

*Orji Sunday is a Nigeria-based journalist who covers environment, politics, conflict and development. Find him on Twitter @orjisunday32.

Español

Español

Português

Português