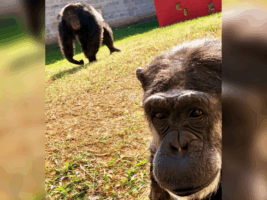

Elena Liberatori, the judge who made history with the case of orangutan Sandra

Jueza Elena y Sandra

Jueza Elena y Sandra

By Pedro Pozas Terrados (executive director GAP Project Spain)

From a very young age, Elena has always had an extraordinary sensitivity and empathy towards non-human animals and this has marked her existence in the defense of life, which she has more than fulfilled in her profession as a judge in Argentina. She is an approachable and open person, with a lot of sympathy and great experience in a courtroom where she has to deal with many complicated and important cases.

The arrival of the “Sandra” case and her subsequent sentence were an important point of reference in the world in defense of animals, especially non-human hominids. In various international legal cases on animal protection, most of them refer to the sentence of the orangutan Sandra, declared by her to be a “non-human person” and therefore with acquired rights. Her decision was supported by several scientists and she has studied the culture and behavior of her species and other studies related to great apes intensively.

INTERVIEW WITH ELENA LIBERATORI

First of all, I’d like to thank you for taking the time for this interview and, of course, for the sentence that went around the world declaring a non-human hominid, in this case Sandra, to be a “non-human person with acquired rights”. When you handed down the sentence, did you imagine that it would be publicized throughout the international media?

It’s worth pointing that the court of which I am the head is an administrative court, i.e. it has jurisdiction over matters of conflict between individuals and the state. In our case, the State of the Autonomous City of Buenos Aires. This means that, at the same time as Sandra’s case, there were many other legal cases in progress and, in that particular year, 2015, I was in charge of another court of first instance, in which I resolved a very important and voluminous case. By this I mean that the case of Sandra, the orangutan from the old Buenos Aires zoo, was just another case with its own particularity from the start, because it was about her, a non-human animal.

Honestly, I never thought about the international repercussions because I always thought that I only did what was appropriate as a judge and what was obvious in my convictions. We began to realize with my team (we network as Equipo Judicial Sandra) that I was making noise, as we say here, when a magazine in Spain declared me Persona No Grata. That magazine is called Mundo Toro. Today, it is still my greatest pride. And at the same time, I was surprised at how quickly they warned me that the decision to declare an animal a “non-human person” could have undesirable consequences for them. It surprised me at the time. However, shortly afterwards, I would say at the beginning of 2016, my team and I were very surprised by the growing international interest in this decision. So much so that we started putting together a clipping with news from incredible countries such as Pakistan, India, Indonesia and South Korea. The fact that we managed to arouse interest in this subject in these distant countries, as well as in other countries in Europe and America, was a great surprise to us. We couldn’t believe it.

As a highly experienced specialist judge, were you surprised that a Habeas Corpus was presented to Sandra?

Habeas Corpus is a procedural route in the criminal jurisdiction. Therefore, in the court I am in charge of, Sandra’s case was processed via Amparo, which is a constitutional way of defending fundamental rights violated by the City of Buenos Aires. That’s a technical clarification, so to speak, and going on to the question, I can say that I keep vivid in my memory the moment when the Secretary of the Court, Dr. Noelia Villarino, came to my office to tell me that this was a file whose author… was an animal!

On behalf of the Great Ape Project, I presented several reports. Did they have any influence on your decision?

Indeed they did. There was a Great Ape Project report against Sandra’s transfer to Rainfer in Madrid, and another report, in this case positive, regarding taking her to the Great Apes Sanctuary of Sorocaba, in Brazil.

It’s important to clarify that although these reports gave me a valuable opinion, all my decisions were based on what the scientific team (made up of veterinarians, biologists, anthropologists, etc. from the National Universities of Buenos Aires and La Plata) assessed. In fact, to decide the best place for the transfer, the team exhaustively established a series of requirements, and whoever met most of them would be the best place to take Sandra. For example, in relation to Sandra’s receiving institution, they asked: is it a scientific institution, what are its publications, is it dedicated to a specific species, does it act as a depot for animals of different species, what legislation is it subject to and does it comply with it; in relation to space, enclosure area, divided into covered and uncovered, usable enclosure volume, divided into covered and uncovered, practicable space for isolation (privacy zone), whether there is a containment area. If there is a containment area, indicate its area and specify its characteristics. Structures in each of the areas, dimensions, proposed function and maintenance of each of them, structure that provides three-dimensionality, what percentage of three-dimensionality it has. The extreme containment area should be for one-off practices, not for daily confinement or overnight stays.

On management: daily routine proposed for Sandra, caregivers and operators, medical facilities, protocols, caregivers and operators, records to be kept, type and frequency, enrichment, training, interaction and research programs, indicating caregivers and operators respectively. On the supervision of Sandra’s living conditions: visiting regime proposed by the institution, reporting regime proposed by the institution. On the social aspects: animals with which she will interact, if any. Procedure for introducing Sandra to the existing group, variables that will be monitored to control these interactions, planned interventions based on the relationships between the animals, circumstances in which they would be carried out.

The scientists pointed out to the court that these information would allow me to compare Sandra’s possible fates, so that I could choose the one that would comply with the court order. On the other hand, at the time, I stated that the institutions presented as candidates should respond to each item in the form of an affidavit. I don’t want to go into too much detail, but my aim is to illustrate the emphasis and importance I gave to the scientific aspects from the very beginning of the case. This is, to this day, a distinctive feature of the work of a tribunal.

I believe that if this case had been directed to a man, perhaps we wouldn’t be talking about Sandra’s liberation. Women are more sensitive, more empathetic and more open. With the chimpanzee Cecilia, the other case of a non-human hominid declared a being with rights, it was also a woman judge who established a favorable sentence for her. It was also women who introduced us to the culture of gorillas, chimpanzees and orangutans, in the persons of Diane Fossey, Jane Goodall and Biruté Galdikas, respectively. What do you think of that?

I don’t think it’s accidental. Women are given caring roles, we express our emotions and feel empathy for others more easily. I think this is all part of the patriarchal societies we live in, which associate men with strength, since they don’t feel empathy for suffering. In this respect, I think we are more evolved…

When Sandra’s case came to you, what did you think? Did you consider it just another case? Was it complicated?

It wasn’t just another case. On the contrary, it was and is a unique case. I was very lucky in that sense, because I wanted to become a lawyer at the age of 14 to defend innocent beings. And non-human animals are an absolute paradigm of innocence. Children too, of course, but the difference is that they have a state institution that looks after them, defends them, protects them and gives them a voice. Unfortunately, none of this happens with non-human animals. And with regard to the other part of the question, this has never been a complicated case for me. Perhaps because from day one my decision had to be made, even if I didn’t know how I was going to get there. In this sense, I am always particularly grateful to the biological scientists Héctor Ricardo Ferrari and Aldo Giúdice, whose knowledge was the guide and the light in the tunnel of our ignorance.

I suppose your colleagues on the court were a bit surprised and expected what you might do, that is, reject the HC. Did they make fun of the situation?

That’s a very interesting question. All the people who work with me were surprised, but they also thought it was the right court for the purposes of the case. On the other hand, I had never seen an orangutan (I’ve always hated zoos) and certainly none of us really knew this non-human animal. When we discovered that we had a very close genetic relationship, sometimes, jokingly and knowing that some people would get annoyed, I would ask for the “relative’s” file. I assume that in many court decisions I have been disruptive, so to speak, and consequently some of my collaborators, at least some of them, may not have liked it That year 2015 was a presidential election year and therefore there were jokes that the “monkey” was also going to vote. This led to the need to expressly clarify that it wasn’t about our rights, but hers, an individual of a different species and with sensitivity.

I hope that your colleagues have seen in the sentence you established with Sandra a way of continuing along the path of empathy with non-humans who also suffer…

I share that hope and I think that’s why I’m so often admired and surprised because, as I said before, I don’t find anything exceptional. I just recognize the scientific evidence. They are beings who suffer. Throughout history we have used them for clothing, entertainment, experimentation, transportation and food. I wonder if there is any area of our lives that doesn’t involve the suffering of animals.

Speaking of the Great Ape Project, what is your opinion of our work, our fight for non-human hominids, in defense of their habitat and indigenous populations?

I greatly value the activity you carry out, despite so much indifference and adversity on the part of those who force us to take on these struggles. And I’m also aware of all the support for the indigenous peoples’ collectives here in Argentina. We owe them another great debt. Not long ago, a high court in an Argentinian province ruled that the Mapuche are not Argentinians.

In Spain, the government already has a law to legislate on great apes, in which, among other things, we call for an end to captivity programs for endangered species in zoos, on the grounds that this is a fraud. What do you think? Do you think it’s necessary and do you support it?

I think it’s great, it’s necessary and I support it fervently. Whenever we have the opportunity to show our solidarity and support for these causes, we do so. Also in the activism we carry out as Equipo Judicial Sandra. Zoos don’t educate, they don’t research, they don’t conserve. They are business models. In this regard, it’s interesting to mention an Argentinian documentary called Zoophobia, in which this is developed. In addition, the tireless work of Proyecto Galgo Argentina with regard to marine animals in captivity should be known. Fortunately, there is significant activism here in Argentina. It should also be noted that the country’s law faculties have an Animal Law department or institute and that the bar associations also have one.

Do you think zoos need to be reconverted? That the citizens of the world need more culture to understand that those in cages are suffering and that it is neither culture nor science to keep beings whose culture and freedom have been amputated?

Zoos don’t need to exist. I don’t believe in any reconversion if they keep non-human animals in captivity. As far as education is concerned, I believe that this is the way forward. In this sense, I have in mind the constitutional reform promoted by the Mexican organization Va por sus Derechos (Go for Your Rights), so that educational content has a non-speciesist perspective. Another valuable attempt, although it has not progressed, is the constitutional reform in Chile.

Finally, would you like to send a message to society, to our young people and to future generations?

I have high hopes that young and future generations will already be living in a changed reality. I won’t see it because the laws of biology prevent me from doing so. But I am very hopeful that one day, not too far away, we will have reformulated the human-animal bond based on respect, affection, empathy, gratitude and admiration, because they are wonderful beings who deserve all of this.

Once again, thank you for this opportunity.

Español

Español

Português

Português