Bacteria, monkeys and men

By Drauzio Varella

The evolutionary process of our species was not lonely. In the intimacy of our viscera, trillions of bacteria followed the same track as long as we go down the trees in the savannas of Africa.

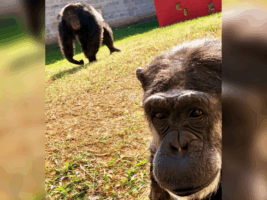

In the course of millions of years, we have lost some germs that persist to this day in our closest relatives: chimpanzees, bonobos and gorillas. It is likely that these changes in the composition of the bacterial flora, which gave rise to the current human micro biota, explain disparate problems such as obesity, some cancers and mental disorders.

For years we want to know if we have inherited from our arboreal primates ancestors germs that inhabit us, or if they were purchased on the environment.

Research with faecal bacteria in mammals suggests that it is more likely the heritage of the participation of the environment. Some scholars, however, suggest that diet and antibiotics have exercised decisive influence on the natural selection of bacteria that survived in our digestive tract.

To answer these questions, Andrew Moeller, from University of California, studied isolated bacteria from fecal samples of 47 chimpanzees in Tanzania, 24 bonobos in the Democratic Republic of Congo, 24 gorillas in Cameroon and 16 people from Connecticut, in the United States.

In collaboration with researchers at the University of Texas, the DNA sequences were compared to a frequent gene in bacteria inhabiting the intestines of great apes (including humans). From these sequences, it was possible to draw the family tree of bacteria.

The conclusion is that they originated in a common ancestor of all great apes that lived 15 million years. As the strain of this ancestor diverged, yielding chimpanzees, bonobos, gorillas, orangutans, and humans, the bacteria in their intestines co-evolved in parallel (cospeciation) to adapt to the differences in diet, habitat and diseases of the digestive tract of the new species.

In recent days, these germs fine-tuned, allowing them to adapt to the immune system of the host, to influence the development of intestinal cells and to modulate our moods and behaviors.

After the great apes diverged, some left behind bacteria that persisted in others.

In another experiment, the group focused on human micro biota. They compared the same DNA sequences previous search, this time in people from Connecticut and from Malawi, Africa.

They showed that the DNA sequences of bacteria present in the intestines of Africans and Americans diverged 1.7 million years ago, a time corresponding to the first exodus of the African continent made by our ancestors.

Interestingly, certain intestinal bacteria present in the Malawian – and in chimpanzees and gorillas – are not found in the US people, highlighting the influence of diet and lifestyle in reducing the micro biota diversity found in industrialized societies.

Source (in Portuguese): http://drauziovarella.com.br/drauzio/artigos/bacterias-macacos-e-homens/

Español

Español

Português

Português